Taming the Bull: The Challenge of Calming Down When Triggered

Calming down when you’re triggered can feel like trying to tame a wild bull 🐂 by inviting it to enjoy herbal tea 🍵. The angry bull doesn’t listen!

The moment something lights your fuse, your brain’s alarm system, the ever-dramatic amygdala, slams down on the panic button 🚨. Your sympathetic nervous system kicks in blasting your body with adrenaline and cortisol which harm the functionality of your immune system.

Negative thought patterns erupt like when Mentos dropped into a Coke bottle 🍬 + 🥤 = 💥sparking a surge of harsh self-talk and catastrophic thinking, sending emotional distress bubbling all over the place.

Now, your heart’s beating like it’s in the final sprint of a 100-meter dash 🏃♂️💨, your blood pressure’s playing the role of a hot air balloon, and your stomach’s churning like a washing machine stuck on a high-speed spin cycle. You’re primed to either fight 🥊, flee 🏃, or freeze ❄️, while your brain has effectively locked away your rational side in a back room.

Your window of tolerance narrows shrinking your capacity to handle stress and regulate emotions. Finding your way back to a steady ground feels like trying to squeeze an elephant 🐘 into a suitcase. Maybe it is possible, but not without serious effort and a bigger suitcase.

Understanding the Amygdala Hijack and Our Quick-Draw Reactions

This reaction taps straight into what Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman calls our “System 1” thinking in Thinking, Fast and Slow. the brain’s quick-draw mode, primed for impulsive, survival-first responses. System 1 seizes the reins like a race car driver on a tight curve, leaving the slower, more thoughtful “System 2” in the dust. While System 1 revs up for action, System 2—the voice of reason, the one that might suggest, “Hey, let’s think this through” gets sidelined, and benched like an unused backup player.

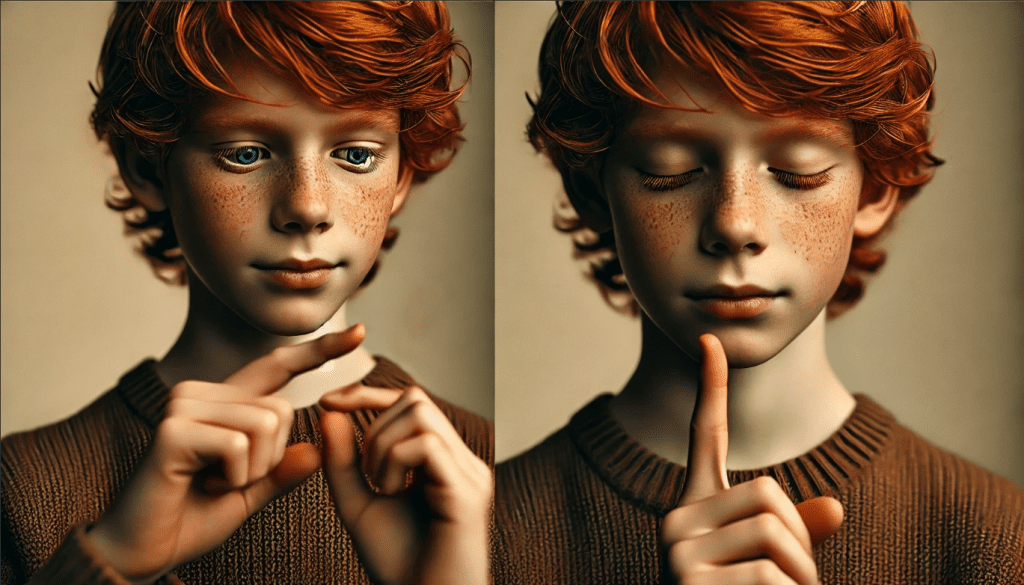

For a hot-blooded, fire-tempered redhead like me (yes, I was a Ginger 🙂), equipped with ADHD and a fuse shorter than a matchstick, getting reactive feels almost like a reflex. I realized, though, that if I wanted to stop detonating at the slightest provocation, I’d had to master the art of self-regulation.

Teaching/Learning the Art of Self-Regulation

“We Teach What We Need to Learn” – Richard Bach

Carl Jung believed that “only the wounded physician heals,” meaning that we are often drawn to guide others in areas where we ourselves seek understanding, transforming our wounds into a source of wisdom and empathy by serving others.

Knowing I wasn’t alone in the struggle to keep my cool, I decided to kill two birds with one stone: I signed up for certification in Emotional Intelligence Course with a company called “Six Seconds“. It was a chance to get a handle on my impulses while picking up tools to help others wrestle with theirs.

Their first lesson on handling the amygdala hijack? Pause for six seconds, just like the name of their company. They claim that’s all it takes to let stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline start to dissipate. According to their model, those six seconds create just enough room to break the cycle of automatic reaction, giving you a shot at responding thoughtfully rather than reacting on impulse.

Six seconds? My parents always said to count to ten, but honestly, I rarely made it past three! Sure, six seconds sounds like a 40% discount, but it’s still twice as long as my fuse can handle. The trick, it turns out, was to take a deep breath, and then another, and another, until I could feel the pressure ease up. Do you think it worked?

Smelling the Flower: A Calming Ritual 🧘

When I shared with my mentor and partner, Lenny Ravich, the need to design a ritual to hit “pause,” he handed me a metaphor that was pure elegance: “Smell the Flower.” 🌸I loved it so much that I started teaching it to leaders and managers everywhere. I’d have them imagine holding a beautiful flower, breathing in deeply to savor its scent, and then exhaling with a gentle sigh. Then, we’d repeat—with a slower, sexier sigh—and voilà: six seconds of calm in the middle of chaos, plus a smile as the bonus.

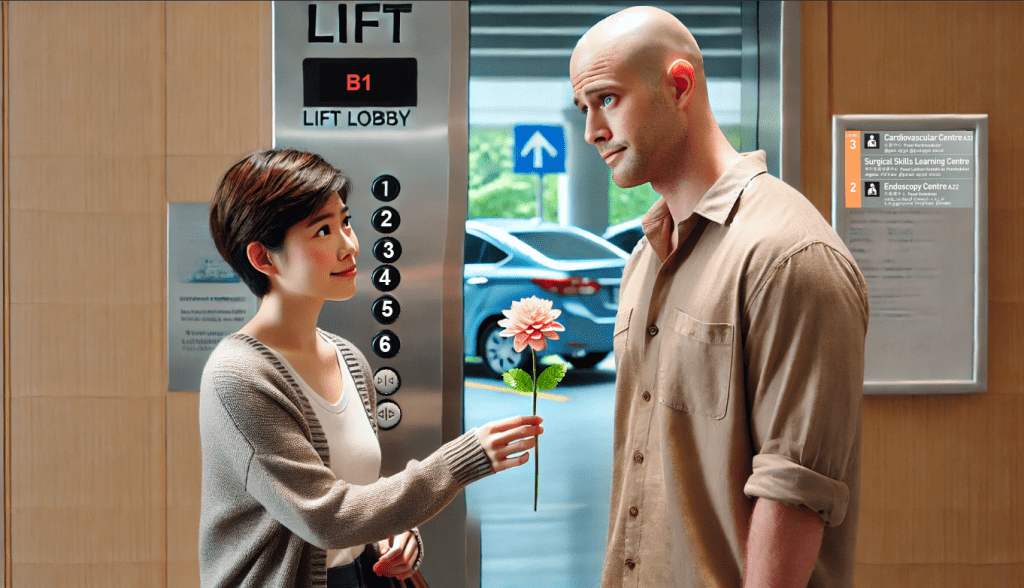

Real-Life Test: Staying Calm at the Hospital

Then, one day, I was invited to train caregivers at KTPH Hospital in Singapore. I invited Sha-En Yeo, a rising star in Positive Psychology to join me to explore offering joint work to the HR team. We were on our way from the car to the lobby when, out of nowhere, a police car 🚔barreled through the parking lot. Maybe it was only 20 or 30 km/h, but in the narrow space, it felt like a high-speed chase. Immediately, I could feel my blood pressure spike. I was a few millimeters away from becoming a patient instead of a trainer, on the verge of marching over to “teach” that reckless driver a lesson. Smell the flower? Yeah, right. That technique was nowhere in sight.

Then, just as I was about to explode, Sha-En, who had seen me teach “Smell the Flower” to the top 250 leaders at Marina Bay Sands, tapped my shoulder. She held out an imaginary flower, looked me right in the eye, and, with a gentle smile, whispered, “Avi, smell the flower.” I smiled and instantly calmed down.

Six Seconds to Pause: Myth or Science?

This incident threw me back to the drawing board. The six-second technique is not working at least not on me. Research into the technique’s validity reveals significant criticism, particularly around its scientific precision. Critics argue that the six-second pause oversimplifies the brain’s complex stress response. Adrenaline and cortisol don’t simply dissipate in a few seconds; while their levels may start to taper off, they can continue affecting the body for minutes or even hours.

Additionally, while deep breathing can engage the parasympathetic nervous system, this effect may vary from person to person. Factors like one’s baseline stress level, personality type, and prior exposure to stress and trauma can impact how effective a brief pause is. For some, it’s a reset; for others, it barely scratches the surface.

The lesson from that police car incident and Sha-En’s graceful intervention was crystal clear. Calming ourselves in the heat of a trigger is a tall order, but a gentle nudge from someone who truly cares can make all the difference in defusing an amygdala hijack.

The Power of Support: Friends, Colleagues, and a Gentle Nudge

Let’s face it—we all need those trusted friends and colleagues to swoop in and save us from ourselves when we’re on the edge. They’re our emotional safety nets, catching us just as we’re about to leap off the ledge of our impatience. And the beauty of it? We get to be that trusted friend for them, too, stepping in with a steady hand when they need it most.

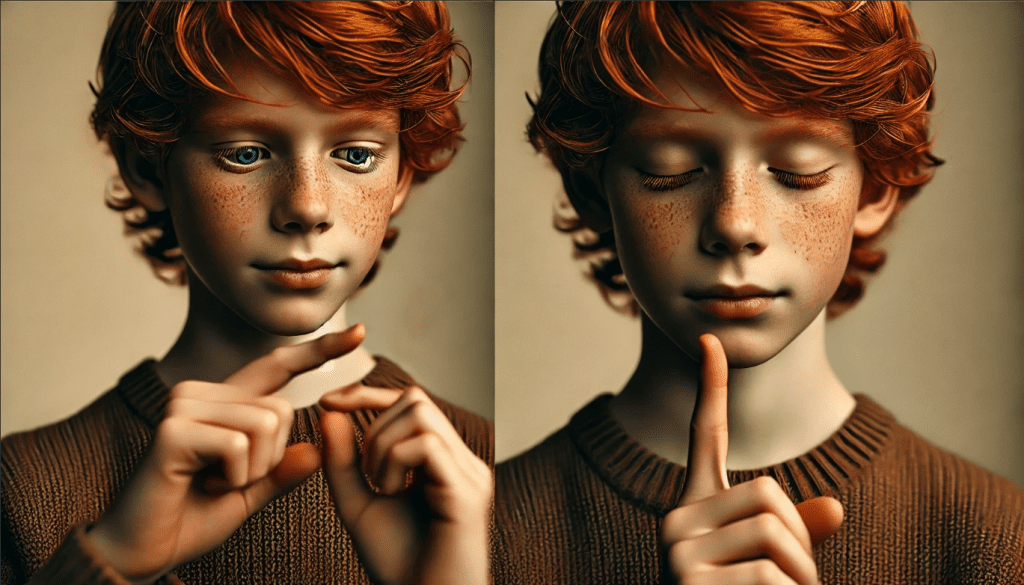

Since then, I’ve turned this into an exercise in my workshops, inviting participants to wander the room and offer each other an imaginary flower to “smell.”

But here’s the catch, tone and gesture matter. There’s nothing quite as aggravating as being told to “calm down” with a bossy tone and a stiff gesture, especially when the other person is already on edge!

So, I suggest a softer approach. Don’t shove that imaginary flower in someone’s face; instead, offer it gently, like a small gift. Put your right hand on your heart, now gently, and hand the imaginary flower from your heart towards their nose. Take a calm breath, and, with warmth, say, “I care about you. Please, smell the flower.” This makes it a gesture of support rather than command, creating a safe space for connection and calm.

Lessons from Healthcare: Resilience and Calm in High-Stress Professions

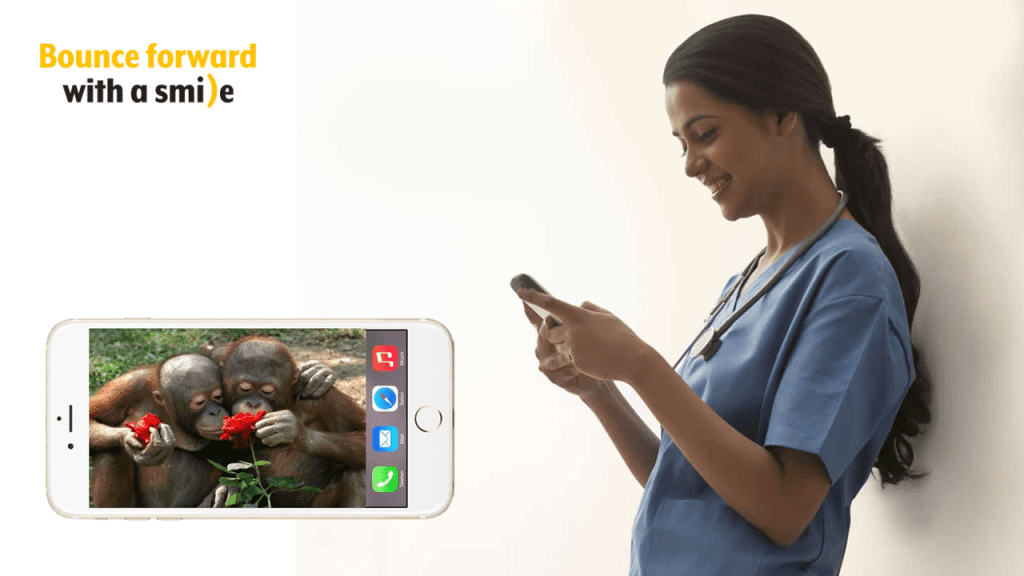

Over the years, I’ve had the privilege of giving talks and holding workshops for many healthcare teams, including teams of incredible nurses 👩⚕️. To me, nursing stands out as one of the most demanding, high-stress professions in the world. Nurses work long hours, often with a level of responsibility that would make anyone’s head spin. They’re accountable for patients’ lives yet they’re not compensated at the level of doctors. Their work is intensely physical and mentally exhausting, and they answer to not one, but four types of “bosses”: senior nurses, doctors, patients, and perhaps the toughest of all—the patients’ families, who often feel their loved one is the top priority and don’t hold back in making that known.

One of the nurses who completed our resilience program, “Bounce Forward With a Smile,” shared a powerful strategy for supporting colleagues facing difficult situations with patients’ families. When they see a fellow nurse being bullied by a patient’s relatives, they find a way to pull her out of the tense interaction. Sometimes, they’ll call her away to “attend to an urgent matter” and, once outside, offer a gentle reminder to “smell the flower.” Other times, they send a quick WhatsApp message with a flower photo and an encouraging text such as, “Don’t take it personally; they’re in pain” or “It’s not about you. just take a deep breath and smell the flower.”

On the lighter side 😀

- In my workshops, I always get a laugh when I say, “If you’re allergic to this imaginary flower, feel free to choose a different one!”

- A month after one session, I got a call from a client, the CEO of a major retail chain in Europe. She said, “Avi, the situation was so intense, I didn’t just smell one flower. I imagined an entire container full of flowers!”

- Turns out, “Smell the Flowers” isn’t as universal as one might think. During a workshop in the Philippines, I was advised to switch it to “Smell the Roses” for a better local fit. It’s fascinating how a minor rephrase can transform a metaphor to respect cultural boundaries.